On 16 January this year, the media fraternity in Tanzania woke up to a rude shock: the two-month-old government of President John Magufuli had permanently banned a newspaper.

In an unprecedented move, the government also made sure that the Kiswahili publication, Mawio, would not be brought out electronically. In the past, suspended newspapers had taken the online option. This time, due to the use of the Electronic and Postal Communication Act, this was not to be.

In an interview, the Minister for Information, Culture, Arts and Sports, Nape Nnauye, accused the paper of publishing “incendiary” and “inflammatory” content that put the peace, stability and security of the country at risk.

In particular, he cited two recent stories on the tense situation in the semi-autonomous archipelago of Zanzibar. In the words of Tanzania Editors Forum (TEF) Secretary-General Neville Meena: “The minister, who is the ultimate boss, has powers to be the complainant, jury, judge and hangman. And if he bans a newspaper or radio station, the law does not provide a mechanism for appeal.”

Ominously, the banning of Mawio coincided with the state regulator, the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA), issuing notices of deregistration to 20 radio stations and eight TV stations for failure to pay their statutory fees on time.

Though we have covered a lot of ground since the mid-1990s, when the media landscape in the country was liberalised, there is still a long way to go. And this applies to both the legal and regulatory framework and the performance of the media itself.

Ethical lapses

Ethical challenges for the media can result from having poorly trained journalists or corrupt editors on staff, a legal regime in place that enforces self-censorship, and the weak economic conditions many outlets operate under. Most media are poorly capitalised and do not pay staff well and promptly, leading to what is commonly referred to as the “brown envelope syndrome”, where media practitioners accept freebies from sources.

Under such conditions, objectivity, fairness and balance suffer.

During the October 2015 general election, major political parties had journalists embedded in presidential candidates’ entourages, with the parties paying all or most of their expenses. Inevitably, TV, radio, newspaper and online reporters filed stories that at times sounded like propaganda for the candidate they were covering.

When a journalist refused to toe the party line, as did a Mwananchi reporter embedded in the campaign of ruling-party candidate John Magufuli, he was asked to leave. However, Mwananchi is an established media house and continued independent coverage of the ruling party campaigns using stringers and bureau chiefs around the country.

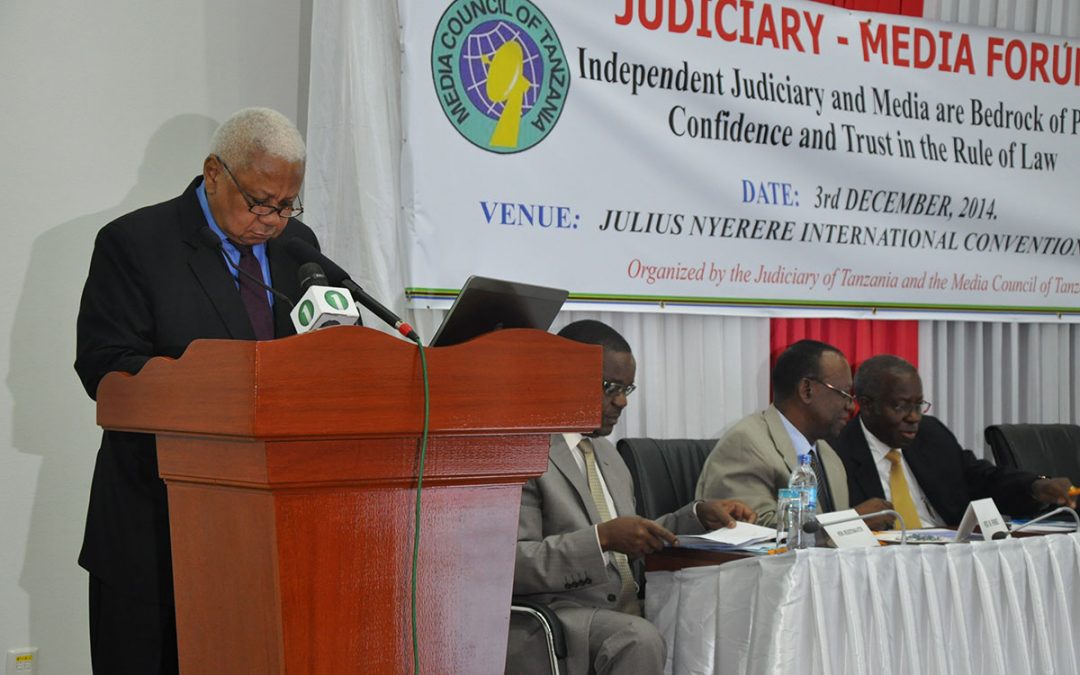

Other ethical lapses the Media Council of Tanzania (MCT) has identified over the years include a lack of impartiality in coverage of court cases, where headlines and content tend to convict people who are still standing trial. The MCT and the Tanzanian judiciary have even started a forum bringing together senior magistrates, judges and editors to discuss professional issues. The MCT has also published guidelines for court reporters.

Coverage of gender, children, and the disabled is another challenging area, and the MCT has conducted training and published manuals and guidelines for journalists on these subjects.

Getting better, slowly

As a result, the Tanzania media has seen improvement around ethics, as shown in a study commissioned by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). However, according to veteran editor Hamis Mzee, there’s still a way to go.

“We are not yet there! Despite improvements, independence, truth and even accuracy are commonly contravened,” he said.

Dr Ayub Rioba, Associate Dean of the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Dar es Salaam, decries practices such as the reporting of unsubstantiated rumours, sensationalism, stereotyping and “mule journalism”, where reporters or even editors are paid by sources to write or slant stories in their favour.

He proposes training and retraining, enhancing self-regulation within newsrooms, including effective post-mortems, and appointing in-house mechanisms that would censure rogue practitioners while rewarding the best, and rooting out unprofessional hacks.

Providing media practitioners with exposure to other African countries with higher standards, paying them well and ensuring they have the tools they need, will also go a long way towards boosting the quality of their work.

The MCT will continue to oversee and promote ethical conduct and media accountability and to raise standards and professionalism in the media in line with its mandate. It was established by the media industry in 1995 as a voluntary, independent and self-regulatory body to counter government intentions to set up a statutory organization.

On a practical level, the MCT acts as a mechanism to assist the public in adjudicating grievances against the media without resorting to expensive court proceedings. This has proved quite successful: it is fast, inexpensive and effective, with a compliance rate of 90 per cent in mediated and arbitrated cases.

Attempt to impose a heavy hand

However, the government has not given up on establishing a statutory body to control the media’s professional and ethical conduct. In 2015 it attempted to rush through Parliament a Media Services Bill that sought to do away with the press freedom gains made in the country thus far. The bill included punitive measures that would have effectively criminalised independent journalism as we know it.

Among other things, the bill stipulated hefty jail terms for ethical lapses (a minimum five-year prison sentence), provided for the state licensing of journalists, forced private broadcasters to broadcast the 8 p.m. evening news bulletin of the state broadcaster, allowed the confiscation of assets of offending media houses and granted wide-ranging enter-and-search powers to junior police officers, including the confiscation of computers and other equipment and material.

It took urgent action by all 11 members of the Coalition on the Right to Information (CORI) – led by the MCT – to stop the bill.

The struggle for a free, professional and independent media in Tanzania is therefore far from over. Whether we will succeed depends on the speed and capacity of the media to adequately develop the professional and ethical reporting skills of journalists, as well as the ability of politicians to curb their appetites for power and refrain from suppressing media freedom in the country – too often under the guise of curtailing “irresponsible journalism”.

Kajubi Mukajanga is the Executive Secretary of the Media Council of Tanzania.

This article is an adaptation of a piece that originally appeared in the AFRICAN FREE PRESS, a MISA project supported by DW AKADEMIE.