(Cartoon by Zapiro. All rights reserved – For more Zapiro cartoons visit www.zapiro.com)

Increasing restrictions on free speech – in the name of “national security” – are occurring across Africa. Journalists and civil society should investigate and mount campaigns against this development.

National security is a term many governments use and abuse to limit basic human rights, including media freedom and broader freedom of expression rights. In doing so, they increasingly cite the growing number of terrorist attacks around the world.

Yet, there is little basis for Southern African governments in particular to raise the terrorism red flag. The sub-region has largely escaped the scourge that has plagued countries to the north. No country has experienced the kinds of attacks seen in Mali and Burkina Faso recently. None have their own versions of Al Shabaab or Boko Haram.

Why the obsession with national security in the Southern African Development Community region then? South Africa offers some important clues to this troubling question.

The South African apartheid regime repressed liberation movements on the grounds of national security. The former State Security Council, the highest decision-making body in the government, was led by a powerful group of military generals. With the transition to democracy, leaders were determined to prevent national security from being abused again.

The new constitution’s drafters decided to place the security cluster – the police, the intelligence services and the military – under civilian control. The police were de-militarised and the intelligence services made accountable to Parliament and subject to investigation by an independent Inspector General of Intelligence.

Backsliding toward the bad old days

Over the past two decades, however, democratic controls over South Africa’s security cluster have weakened. There is growing evidence that security forces are being put to anti-democratic uses.

The most visible manifestation of this has been an escalation in police violence against public protests – culminating in the 2012 Marikana massacre, when the police shot and killed 34 mine workers during a violent strike and wounded another 78. It was the deadliest use of force against civilians in a single incident by South African security forces in over four decades.

There are also other signs that a process of “securitisation” is under way. The government is treating more and more social problems as threats to national security.

The government is increasingly deploying the military jointly with the police on domestic operations. This is in spite of the fact that a 1996 report strongly discouraged domestic military deployment on the basis that this amounted to the unacceptable re-militarisation of society. Arguments have emerged for a massive increase in the military budget, using the military’s expanded domestic role as a reason, despite the fact that the country faces no major threats to its territorial integrity. The once powerful defence industry is seeking to re-establish itself as a major economic player.

The South African Police Service (Saps) has also shown signs of a creeping re-militarisation in terms of organisational design, operational functions, institutional culture, weaponry and even uniforms.

The foreign and domestic branches of the intelligence services were centralised into the State Security Agency (SSA) in 2009. The SSA was formed without the necessary democratic checks and balances. The SSA has a political-intelligence gathering mandate, which means that it can conduct surveillance on politicians within and beyond the ruling party. This very broad mandate is open to abuse.

Recently, the Inspector General’s office has been deprived of resources and independence, and there are signs that the government aims to appoint an obliging party cadre to this important office.

The Inspector General has confirmed that the intelligence services use mass surveillance technologies, in spite of growing opinion that mass surveillance leads to unjustifiable invasions of privacy. While there are signs of intelligence overreach, these services do not appear to be paying attention to more genuine threats to national security, such as the outbreak of xenophobic attacks on African and other foreign nationals who migrate to the country.

Harassment of critics

While democratic controls of the security cluster still remain largely intact, there are signs that an increasingly authoritarian South African government is using technologies and practices developed during the war against terror to monitor, harass and even suppress perceived critics.

For instance, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) and the United Front (UF) – both involved in the creation of a left alternative to the ANC – claim they have been spied on simply because of their political activities. Social movements have been complaining for over a decade of harassment by intelligence services.

Journalists are also among the perceived critics. Since 2008, the intelligence services have periodically placed journalists from the Sunday Times and the Mail & Guardian newspapers under surveillance, attempting to uncover their confidential sources. Sources are drying up, too scared to speak in case their identities are revealed.

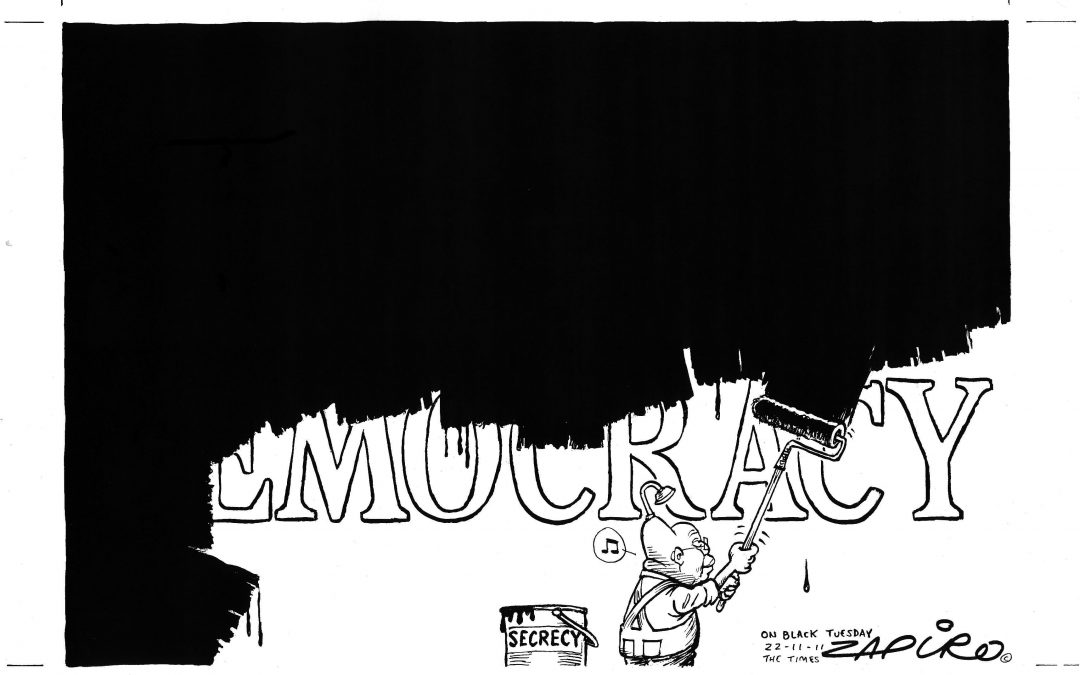

Secrecy bill and classified info

Independent investigative journalism on security cluster activities in South Africa is needed more than ever. However, the presidency is set to sign a Protection of State Information Bill (the ‘Secrecy Bill’), which will make it extremely difficult to source the facts and information needed for these stories.

The bill will require that the security cluster classify information, and anyone found leaking or publishing that information (including journalists) may be jailed. The grounds for classification remain overly broad; the classification and declassification processes lack independence and transparency; and the defences for disclosure of information remain inadequate. The bill is therefore likely to reduce what little transparency exists in this sensitive area of government, which means that abuses could become more frequent.

Learning the lessons from “democratic” South Africa, journalists and civil society across the continent need to investigate and mount campaigns against the expansion of security cluster activities and classification of information purportedly in the interests of “national security”. The term is so nebulous that governments can invest it with whatever meaning they see fit.

Regarding classification, no one should accept the argument that because an issue concerns national security, information must be kept secret. Only if there is a real and substantial threat of harm if information is released should it be kept out of journalists’ hands.

Edward Snowden’s information leaks, and subsequent reporting on these by courageous journalists like Laura Poitras and Glen Greenwald, showed that the most powerful national security state in the world could be confronted successfully. Their work has forced reforms to the US’s mass surveillance programme. With a concerted effort by the region’s journalists to turn the national security arena into a dedicated beat, there is no reason why similar victories can’t be won here.

Jane Duncan is Professor in the Department of Journalism, Film and Television at the University of Johannesburg. She is the author of “The Rise of the Securocrats: The Case of South Africa”, published in 2015.

This article is an adaptation of a piece that originally appeared in the AFRICAN FREE PRESS, a MISA project supported by DW AKADEMIE.